Surgery-related factors for pancreatic fistula after pancreatectomy: an umbrella review

Introduction

Over the last several decades, tremendous progress has been made in the surgical techniques and perioperative management of pancreatic surgery. The safety of various types of pancreatectomy has improved significantly (1,2). However, postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) remains the leading cause of perioperative mortality after pancreatectomy (3). According to the international study group of pancreatic surgery, the definition of POPF is “a drain output of any measurable volume of fluid on or after postoperative day 3 with an amylase content greater than 3 times the serum amylase activity” (4,5).

POPF has been graded as A, B, and C. Grade A POPFs do not require clinical intervention; therefore, they are called biochemical fistulas, whereas Grade B or C POPFs are referred to as clinically relevant POPFs (CR-POPFs) because they require changes in patient management (4,5). Take the two main procedures of pancreatectomy: pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) and distal pancreatectomy (DP), as examples. Even in high-volume centers, the incidence of POPF after PD ranges from 10–35% (6) while POPF after DP 16–44% (7). Recently, many surgical scientists have reported their experience with POPF, and many risk factors related to pathophysiological features (8-11) and surgical procedures (12-14) have been considered significant predictors of POPF. Compared with unmodifiable factors such as patient characteristics, surgical interventions and perioperative management improvements ensure a better prognosis after pancreatectomy. Therefore, it is important to understand the measures and techniques that can reduce the risk of POPF.

Several published meta-analyses (MAs) have summarized evidence on various techniques to prevent POPF, which include reconstruction of gastrointestinal tract (15), anastomotic techniques (16), extent of surgical resection (17), surgical approaches (18), preoperative or postoperative drainage (19,20), nutritional routes (21) and use of biomedical materials (22). Previous MAs on this topic included either relatively small cohorts (23,24) or data from observational studies (25), which reduced their validity. Furthermore, conflicting data among some MAs (26,27) pose challenges for clinical decision-making. To date, there has been little synthesis on the credibility, precision, and quality of this evidence in aggregates.

Umbrella reviews are specific techniques for comprehensively collecting and evaluating evidence of published MAs on a specific topic to identify the effects with the most convincing evidence (28). It not only assesses the strength and validity of the evidence but also the potential risk of bias. Thus, this study aimed to conduct an umbrella review to investigate the effect of surgery-related factors on POPF to reduce the risk of POPF after pancreatectomy. We present this article in accordance with the PRIOR reporting checklist (available at https://hbsn.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/hbsn-23-601/rc).

Methods

The protocol for this umbrella review was registered at PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42023437139).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) intervention vs. comparison MAs of observational or randomized controlled studies; (II) MAs reporting odds ratio (OR), risk ratio (RR), hazard ratio (HR), and mean difference (MD) as effect sizes and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs); and (III) MAs included ≥2 studies. PICO definitions: (I) Population: adult patients (≥18 years old) with either benign or malignant pancreatic/duodenal diseases qualified for any type of pancreatectomy (e.g., PD, DP, central pancreatectomy, and enucleation); (II) Intervention: surgical-related factors including reconstruction of the gastrointestinal tract, anastomotic techniques, extent of surgical resection, surgical approaches, preoperative or postoperative drainage, intraoperative fluid management, nutritional routes, and use of biomedical materials (Table 1); (III) Comparator: the corresponding control of the above-mentioned surgical-related factors in the original MAs; and (IV) Outcomes: POPF rate after pancreatectomy.

Table 1

| First author, year | Country | Journal | Original article retrieval time | No. of included studies | Individual studies design | Diseases type | Surgical type | No. of patients | Intervention [No. of cases] | Control [No. of cases] | Quality appraisal tool | Conflict of interests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chierici, 2022 (13) | France | HPB (Oxford) | 2021/4/15 | 13 | Observational study | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 1,098 | PD + PDO [472] | PD + pancreatic anastomosis [626] | ROBINS-I | No |

| Andreasi, 2020 (14) | Italy | HPB (Oxford) | 2020/3/11 | 9 | Observational study | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 4,384 | PD with omental/falciform ligament wrapping [1,564] | PD without omental/falciform ligament wrapping [2,820] | MINORS | No |

| Mobarak, 2021 (15) | UK | International Journal of Surgery | 2020/4/8 | 14 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 2,031 | PD + Roux-en-Y reconstruction [728] |

PD + single loop reconstruction [1,303] |

RoB 2 | No |

| Jin, 2019 (16) | China | World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery | 2019/3/15 | 11 | RCTs | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 1,765 | PD + PJ [856] | PD + PG [909] | RoB 2 | No |

| Hajibandeh, 2017 (29) | UK | International Journal of Surgery | 2017/7/9 | 6 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 890 | PD + SA [300] | PD + HA [590] | The Cochrane’s tool, NOS |

No |

| Hai, 2022 (30) | China | Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | 2021/1/9 | 10 | RCTs | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 1,472 | PD + PJ [Duct-to-mucosa] [732] | PD + PJ [invagination] [740] | RoB1 | No |

| Cao, 2020 (1) | China | Asian Journal of Surgery | 2019/4/1 | 6 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 1,409 | PD + modified Blumgart anastomosis [634] | PD + interrupted transpancreatic suture [775] | The Cochrane’s tool, NOS |

No |

| Wang, 2020 (31) | China | Gastroenterology Research and Practice | 2019/6/30 | 14 | Observational study | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 2,596 | Restrictive intraoperative fluid management [1,284] | Liberal intraoperative fluid management [1,312] | MINORS | No |

| Adiamah, 2019 (21) | UK | HPB (Oxford) | 2018 | 5 | RCTs | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD/PPPD | PD/PPPD | 690 | EN [383] | PN [307] | RoB1 | No |

| Peng, 2019 (32) | China | BMC Surgery | 2019/1 | 30 | Observational study | Pancreatic head carcinoma | PD | 12,031 | PD + VR [2,186] | PD [9,845] | NOS | No |

| Kotb, 2021 (17) | UK | Langenbeck’s Archives of Surgery | 2020/5/6 | 5 | RCTs | Pancreatic head carcinoma | PD | 724 | Extended lymphadenectomy [364] | Standard lymphadenectomy [360] | The Cochrane’s tool | No |

| Ironside, 2018 (18) | India | British Journal of Surgery | 2017/8 | 17 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 1,472 | Artery-first pancreatoduodenectomy [771] | Standard pancreatoduodenectomy [701] | Downs and Black checklist | No |

| Crippa, 2016 (19) | Italy | European Journal of Surgical Oncology | 2015/9/13 | 5 | Observational study | Periampullary or pancreatic head tumor | NA | 704 | PBD [metal stents] [202] | PBD [plastic stents] [502] | NA | No |

| Guo, 2022 (26) | China | International Journal of Surgery | 2022/2/26 | 7 | RCTs | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 847 | With pancreatic duct stent [426] | Without pancreatic duct stent [421] | The Cochrane’s tool | No |

| Li, 2023 (33) | China | Asian Journal of Surgery | 2021/9/12 | 12 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 7,918 | EDR [1,781] | LDR [6,137] | ROBINS-I, RoB 2 | No |

| Gachabayov, 2019 (34) | USA | International Journal of Surgery | NA | 6 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 1,519 | PDG [806] | CSD [713] | The Cochrane’s tool, NOS |

No |

| Lyu, 2020 (20) | China | Surgical Endoscopy | 2019/6/1 | 6 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 1,538 | PD + peritoneal drainage [869] | PD + no drainage [669] | The Cochrane’s tool, NOS |

No |

| Ouyang, 2022 (35) | China | Frontiers in Oncology | 2021/7/25 | 9 | Observational Study | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 3,732 | RPD [1,149] | LPD [2,583] | NOS | No |

| Zhang, 2021 (36) | China | Updates in Surgery | 2020/5 | 18 | Observational Study | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 5,795 | RPD [1,420] | OPD [4,375] | NOS | No |

| Yan, 2023 (37) | China | Frontiers in Oncology | 2022/5 | 39 | RCTs, observational study | Periampullary or pancreatic head tumor | PD | 40,230 | LPD [4,262] | OPD [35,968] | MINORS, RoB 2 | No |

| Halle-Smith, 2022 (12) | UK | British Journal of Surgery | 2021/5 | 55 | RCTs | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 7,512 | 22 perioperative interventions [NA] | The corresponding controls [NA] | The Cochrane’s tool | No |

| Kiełbowski, 2021 (8) | Poland | Polish Journal of Surgery | 2020 | 20 | Observational study | Patients with pancreatic/duodenum diseases qualified for PD | PD | 6,225 | 13 factors related to post-operative pancreatic fistula [NA] | NA | NA | No |

| Oweira, 2022 (2) | France | World Journal of Surgery | 2021 | 7 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for DP | DP | 553 | DP + reinforced stapler [267] | DP + standard stapler [286] | NOS, RoB 2 | No |

| Mungroop, 2021 (22) | Netherlands | BJS Open | 2020/4 | 4 | RCTs | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for DP | DP | 893 | With fibrin sealant patch [452] | Without fibrin sealant patch [441] | RoB 2 | No |

| Wu, 2013 (38) | China | Frontiers in Medicine | 2013/1 | 4 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for DP | DP | 200 | DP + PTPS [82] | DP [118] | The Cochrane Handbook | No |

| van Bodegraven, 2022 (39) | Italy | British Journal of Surgery | 2021/1/1 | 5 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for DP | DP | 2,153 | No abdominal drainage after DP [685] | Routine abdominal drainage after DP [1,468] | The Cochrane Handbook, NOS | No |

| Xinyang, 2023 (40) | China | Frontiers in Surgery | 2023/2 | 3 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for DP | DP | 651 | Passive drainage [352] | Active suction drainage [299] | NOS, RoB 2 | No |

| Chen, 2023 (41) | China | HPB (Oxford) | 2021/9/29 | 5 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for DP | DP | 5,343 | EDR [1,050] | LDR [4,253] | The Cochrane Handbook, NOS | No |

| Li, 2023 (42) | China | Updates in Surgery | 2022/6/30 | 34 | Observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for DP | DP | 5,785 | RDP [2,163] | LDP [3,622] | NOS | No |

| Lyu, 2022 (43) | China | Minimally Invasive Therapy & Allied Technologies | 2019/7/1 | 30 | Observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for DP | DP | 4,040 | LDP [1,921] | ODP [2,119] | NOS | No |

| Zhou, 2020 (44) | China | Medicine (Baltimore) | 2020/2 | 7 | Observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for DP | DP | 2,264 | RDP [515] | ODP [1,749] | NOS | No |

| Tang, 2022 (45) | China | International Journal of Surgery | 2021/9/13 | 5 | Observational study | Patients with pancreatic cancer qualified for l-RAMPS or o-RAMPS | l-RAMPS/o-RAMPS | 189 | l-RAMPS [83] | o-RAMPS [106] | ROBINS-I | No |

| Hang, 2022 (46) | China | International Journal of Surgery | 2021/11 | 20 | Observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for spleen preserving DP | Spleen preserving DP | 2,173 | SVP-DP [1,467] | WT-DP [706] | NOS | No |

| Zhou, 2019 (47) | China | BMC Surgery | 2018/7/1 | 5 | Observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for DP/RAMPS | DP/RAMPS | 285 | RAMPS [135] | DP [150] | NOS | No |

| Nakata, 2018 (48) | Japan | Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Science | 2017/2/15 | 15 | Observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for DPS/SPDP | MI-DPS/MI-SPDP | 769 | MI-SPDP [378] | MI-DPS [391] | NA | No |

| Xiao, 2018 (49) | China | HPB (Oxford) | 2017/11 | 8 | Observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for CP/PD | CP/PD | 618 | CP [235] | PD [383] | NOS | No |

| Bi, 2023 (50) | China | International Journal of Surgery | 2022/2 | 26 | Observational study | Benign or low-grade malignant pancreatic body lesions | CP/DP | 2,113 | CP [697] | PD [1,416] | NOS | No |

| Shen, 2021 (51) | China | Frontiers in Surgery | 2021/5/31 | 20 | Observational study | Pancreatic neoplasms | Enucleation/standard surgical resection | 7,073 | Enucleation [1,802] | Standard surgical resection [5,271] | NOS | No |

| Roesel, 2023 (52) | Switzerland | HPB (Oxford) | 2022/3 | 8 | Observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for pancreatic enucleation | Standard open open/laparoscopy or robot-assisted enucleation | 626 | Open enucleation [366] | Laparoscopy or robot-assisted enucleation [260] | ROBINS-I | No |

| Małczak, 2020 (53) | Poland | HPB (Oxford) | 2018/11/29 | 19 | Observational study | Pancreatic cancer | Pancreatic operations with/without concomitant arterial resection | 2,710 | With concomitant arterial resection [263] |

Without concomitant arterial resection [2,447] | NOS | No |

| Lei, 2016 (54) | China | Gastroenterology Research and Practice | 2015/6/1 | 6 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for pancreatic surgery | Ultrasonic dissection/conventional dissection | 425 | Ultrasonic dissection [215] | Conventional dissection [210] | Jadad, MINORS | No |

| Zhang, 2020 (55) | China | Medicine (Baltimore) | 2019/10 | 11 | RCTs, observational study | Patients with pancreatic diseases qualified for pancreatic surgery | With/without polyglycolic acid mesh | 1,598 | With polyglycolic acid mesh [884] | Without polyglycolic acid mesh [714] | The Cochrane’s tool, NOS |

No |

CSD, closed suction drainage; CP, central pancreatectomy; DP, distal pancreatectomy; DPS, distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy; EDR, early drain removal; EN, Enteral nutrition; HA, hand-sewn anastomosis; LDR, late drain removal; LDP, laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy; LPD, laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy; l-RAMPS, laparoscopic-RAMPS; MI, minimally invasive; MINORS, Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies; NA, not available; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; ODP, open DP; OPD, open pancreatoduodenectomy; o-RAMPS, open-RAMPS; PBD, preoperative biliary drainage; PD, pancreatoduodenectomy; PDG, passive drainage to gravity; PDO, pancreatic duct occlusion; PG, pancreaticogastrostomy; PJ, pancreaticojejunostomy; PN, parenteral nutrition; PPPD, pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy; PTPS, prophylactic transpapillary pancreatic stenting; RAMPS, radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RDP, robotic distal pancreatectomy; ROBINS-I, Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies of Interventions; RPD, robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy; SA, stapled anastomosis; SPDP, spleen-preserving DP; SVP-DP, splenic vessels preserving-DP; VR, vein resection; WT-DP, Warshaw technique-DP.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) systematic review without MA; (II) meeting abstracts; and (III) exposure to pathophysiological features [i.e., age, sex, and body mass index (BMI)].

Search strategy

Two researchers (Y.W., N.W.) independently searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. A manual search was also performed for references of eligible MAs. The last electronic search was performed on June 19, 2023. Detailed search strategies for the four databases are provided in Table S1. Discrepancies during the search process were discussed to achieve consensus.

Study selection

Two authors (Y.W. and N.W.) independently screened the results by title and abstract according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Considering that more than half of the published MAs have become out of date after 5.5 years (56,57), we defined 2018 as the cut-off year. If MAs with overlapping associations were found during the abstract screening, those published before 2018 were excluded.

After screening the titles and abstracts, full-text screening of eligible publications was required. There is clear evidence that including MAs with overlapping data leads to a risk of bias and reduces the credibility of results (58,59). Therefore, a citation matrix was used to screen overlapping MAs published after 2017 (60). The corrected covered area (CCA) was used to quantify the degree of overlap in the citation matrix (61). A CCAs index greater than 10% was labeled as having a high degree of overlap (online table available at https://cdn.amegroups.cn/static/public/hbsn-23-601-1.pdf). If the CCAs index was >10%, the MAs with the best AMSTAR2 degree, latest publication date, and largest amount of data were considered. If the CCAs index was <10%, both the MAs were retained.

Assessment of methodological quality

MAs that qualified for full-text screening were approved by one researcher (B.L.) using the AMSTAR2 scale (62). Some items formed critical domains (Appendix 1). According to the provisions of AMSTAR2 scale, the methodological quality of literature can be classified as “High”, “Moderate”, “Low” and “Critically low”. The classification criteria are as follows (62):

- High: no or one non-critical weakness.

- Moderate: more than one non-critical weakness.

- Low: one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses.

- Critically low: more than one critical flaw with or without critical weaknesses.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two authors (Y.W. and N.W.) independently extracted data from eligible MAs. The following data were extracted from each MAs: first author, publication year, country, journal name, original article retrieval time, number of included studies, individual study design, disease type, surgical type, total number of patients included, intervention group and number of cases, control group and number of cases, quality appraisal tool for each MAs, conflicts of interest, outcomes (type of effects model, MA metric, estimates and the corresponding 95% CIs, P value), heterogeneity, and publication bias.

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) was used to quantify the strength of evidence included in this umbrella review. It was proposed by the GRADE Working Group in 2004 (63). This grading tool classifies the quality of evidence into four grades: “High”, “Moderate”, “Low” and “Very low”. This allowed us to classify the strength of evidence for each MA outcome by comprehensively evaluating the data.

It is worth mentioning that umbrella review is not a repeat MA of existing data but an objective and comprehensive approach to the existing evidence on a specific topic (64). To identify heterogeneity, Cochran’s Q test P>0.10 was significant (65). Funnel plots and Egger’s tests were used to detect small study effects (66). Funnel plot asymmetry or Egger’s test P value <0.10 were considered evidence of a small-study effect. For the statistical tests of clinical outcomes, the significance threshold was set at P<0.05.

Results

Study section and characteristics

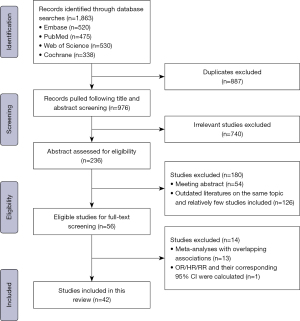

Of the 1,863 unique studies initially identified, we finally selected 42 published MAs [22 only related to PD (1,8,12-21,26,29-37), 2 related to both PD (54,55) and DP, 11 only related to DP (2,22,38-44,46,48), 7 related to other types of pancreatectomy (45,47,49-53)] (Figure 1), including 82 outcomes (Tables S2,S3) on PD (n=54), DP (n=17), radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy (n=3), central pancreatectomy (n=3), enucleation (n=4) and unclassified pancreatectomy (n=1), regarding risk of POPF. A list of studies excluded after full-text screening is provided in Table S4. The 42 MAs were from ten countries, including China (n=25), the UK (n=5), Italy (n=3), France (n=2), Poland (n=2), the USA (n=1), the Netherlands (n=1), Switzerland (n=1), Japan (n=1), and India (n=1). Seven MAs (12,16,17,21,22,26,30) included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) alone, whereas others included observational studies. These included data from 559 original researches involving 147,043 patients (Table 1).

Methodological quality

The methodological quality ratings of the 42 MAs included in this umbrella review are listed in Table S5. Of the 42 MAs, only one Cochrane review (30) was rated as high quality, four as moderate, and the rest of MAs were rated as low (n=16) or critically low (n=21). Overall, the main flaws of the low-quality or critically low-quality MAs failed to meet item 2 and item 7 on the AMSTAR2 scale. In other words, they failed to register a protocol before conducting the MAs and failed to provide a list of excluded studies or justify their exclusion. In addition, 7 MAs were unsatisfactory in explaining the risk of bias in the results of MAs; 4 of 42 MAs did not assess small study effects (publication bias).

Overlapping assessment

Twenty-three MAs on ten topics were found to have overlapping associations between surgery-related factors and risk of POPF. These overlapping associations include the following topics: pancreatic duct occlusion (PDO) or pancreatic anastomosis in PD (13), pancreatogastrostomy or pancreatojejunostomy in PD (16), robot-assisted PD vs. open PD (36), laparoscopic PD vs. open PD (36), enteral nutrition or parenteral nutrition after PD (21), use of reinforced or standard staplers in DP (35), laparoscopic vs. open for radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy (45), splenic preservation PD vs. PD with splenectomy (48), central pancreatectomy or DP for patients with benign/low-grade malignancy localized in the pancreatic neck or body (50) and enucleation or standard surgical resection for small pancreatic tumours (51). Detailed information on the citation matrices and CCA index for MAs with overlapping associations is provided in the online table (available at https://cdn.amegroups.cn/static/public/hbsn-23-601-1.pdf).

Certainty of evidence

Twenty-six of the 82 outcomes (31.71%) were nominally statistically significant (P≤0.05) (Table S3). A total of 32 outcomes (39.02%) showed significant heterogeneity. Only 51 outcomes were assessed for publication bias using funnel plots or Egger’s test, of which 9 reported significant publication bias.

Among the 82 outcomes, six (7.32%) were supported by high-quality evidence. Moderate-quality evidence was found for 13 outcomes (15.85%). The remaining outcomes, with either low-quality [26 (31.71%)] or very low-quality [37 (45.12%)] evidence, are summarized in Table S2.

All-grade POPF after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD)

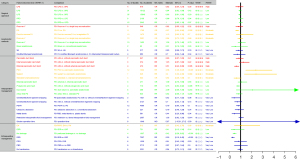

Figure 2 shows the relative effect and their corresponding 95% CIs and the quality of evidence for the association between PD-related factors and the incidence of all-grade POPF. Factors were grouped into four categories: surgical approach, anastomotic method, intraoperative management, and extra-operative management.

As for surgical-approach factors, we observed no clear association with high quality of evidence between open versus laparoscopic PD and incidence of all-grade POPF. Low-quality evidence showed that the incidence of all-grade POPF was not associated with open versus laparoscopic PD, robotic versus laparoscopic PD, or robotic versus open PD.

As for anastomotic-method factors, Roux-en-Y versus single-loop reconstruction was not associated with incidence of all-grade POPF with high quality of evidence. The association between pancreaticogastrostomy (PG) and decreased incidence of all-grade POPF compared with pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ) [OR =0.67 (95% CI: 0.53, 0.86)] was rated with moderate quality of evidence. Duct-to-mucosa PJ versus invagination PJ and Roux-en-Y versus single-loop reconstruction were not associated with the incidence of all-grade POPF, respectively, with moderate quality of evidence. No clear association with low to very low quality of evidence was shown for the association of the incidence of all-grade POPF with Roux-en-Y versus single-loop reconstruction, Braun’s versus conventional anastomosis, stapled versus hand-sewn anastomosis, PJ with modified Blumgart anastomosis, and interrupted transpancreatic suture.

Regarding intraoperative management factors, high-quality evidence was found for the inverse association of the placement of an external pancreatic ductal stent with the incidence of all-grade POPF after PD [RR =0.61 (95% CI: 0.43, 0.86)], whereas there was no clear association between the placement of an internal pancreatic duct stent and pancreatic duct stent (internal and external) with the incidence of all-grade POPF after PD. Moderate quality of evidence was found for the association of increased incidence of all-grade POPF after PD with pancreatic anastomosis with versus without PDO/sealant [PDO: RR =2.38 (95% CI: 1.46, 3.87); sealant: RR =2.40 (95% CI: 1.33, 4.30)], and no clear association of all-grade POPF after PD with standard versus extended lymphadenectomy. We observed no association between the incidence of all-grade POPF after PD and external versus internal pancreatic stenting, pancreatic anastomosis with versus without duct suture, artery-first versus standard PD, PD/PJ with versus without omental/falciform ligament wrapping, PD with versus without vascular resection, ultrasonic versus conventional dissection, restrictive versus liberal intraoperative fluid management, or short versus long operation time in low to very low quality of evidence. In addition, PD with versus without polyglycolic acid mesh and metal versus plastic stents were associated with a decreased incidence of all-grade POPF with low and very low quality of evidence [polyglycolic acid mesh: RR =0.76 (95% CI: 0.62, 0.92); metal stents: OR =0.44 (95% CI: 0.20, 0.96)].

Regarding extraoperative management factors, no association was rated with a high quality of evidence. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition was not associated with the incidence of all-grade POPF after PD, with a moderate quality of evidence. Early versus late drain removal was not associated with the incidence of all-grade POPF after PD with low quality of evidence, but was associated with a decreased incidence of all-grade POPF after PD with very low quality of evidence [RR =0.26 (95% CI: 0.15, 0.45)]. No drainage versus peritoneal drainage was associated with a decreased incidence of all-grade POPF after PD with low quality of evidence [OR =0.42 (95% CI: 0.29, 0.62)]. No clear association with very low quality of evidence was shown for the incidence of all-grade POPF with passive drainage to gravity versus closed suction drainage, PD with versus without preoperative biliary drainage, and PD without versus with transfusions.

CR-POPFs after PD

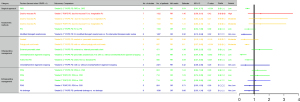

Figure 3 shows the relative effect and their corresponding 95% CIs and the quality of evidence for the association between PD-related factors and the incidence of CR-POPF. These factors were grouped into categories.

Regarding surgical approach factors, only low-quality evidence was found for the inverse association of incidence of CR-POPF after PD with robotic versus open PD.

As for anastomotic-method factors, duct-to-mucosa versus invagination PJ was not associated with incidence of “Grade C” POPF, CR-POPF, and “Grade B” POPF after PD, which was rated as high and moderate quality of evidence. No association between the incidence of CR-POPF after PD and PG versus PJ was rated as low-quality evidence. In addition, very low quality of evidence was found for the association of decreased incidence of CR-POPF after PD with PJ-modified Blumgart anastomosis versus PJ-interrupted transpancreatic suture [OR =0.32 (95% CI: 0.12, 0.84)].

As for intraoperative management factors, moderate quality of evidence was found for no association of incidence of CR-POPF with pancreatic anastomosis with versus without pancreatic duct sealant, but for an inverse association of incidence of CR-POPF with PD with versus without polyglycolic acid mesh [RR =0.50 (95% CI: 0.37, 0.68)]. PJ with versus without omental/falciform ligament wrapping [RR =0.14 (95% CI: 0.04, 0.49)] and artery-first versus standard PD [RR =0.59 (95% CI: 0.37, 0.95)] were associated with a decreased incidence of CR-POPF with low quality of evidence. We observed no association between the incidence of CR-POPF after PD with external versus internal pancreatic stents and PD with versus without omental/falciform ligament wrapping with low to very low quality of evidence.

As for extraoperative-management factors, we saw no association of incidence of neither CR-POPF, “Grade B” POPF, “Grade C” POPF, nor biochemical fistula with passive drainage to gravity versus closed suction drainage with low to very low quality of evidence. Peritoneal versus no drainage was not associated with the incidence of CR-POPF with a very low quality of evidence.

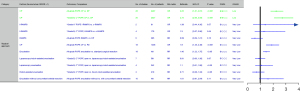

POPF after DP

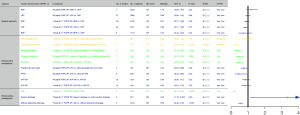

Figure 4 shows the relative effect and their corresponding 95% CIs, and the quality of evidence for the association between DP-related factors and the incidence of POPF. These factors were grouped into categories.

As for surgical approach factors, no high, moderate, and low quality of evidence were found. Very low quality of evidence was found for no association of the incidence of all-grade POPF or CR-POPF after DP with robotic versus open DP and laparoscopic versus open DP.

As for anastomotic-method factors, reinforced versus standard stapler [OR =0.33 (95% CI: 0.19, 0.57)] was associated with decreased incidence of CR-POPF after DP with low quality of evidence.

Regarding intraoperative management factors, moderate quality of evidence was found for inverse association of incidence of CR-POPF with DP with versus without polyglycolic acid mesh [RR =0.31 (95% CI: 0.21, 0.46)], but no association was found between CR-POPF incidence and DP with and without fibrin sealant patch. Low quality of evidence was found for the inverse association of the incidence of all-grade POPF with ultrasonic versus conventional dissection [RR =0.46 (95% CI: 0.27, 0.76)] and the incidence of CR-POPF with minimally invasive spleen-preserving DP versus minimally invasive DP with splenectomy [OR =0.43 (95% CI: 0.25, 0.74)]. Very low quality of evidence was found for the association of decreased incidence of all-grade POPF with DP with versus without polyglycolic acid mesh [RR =0.74 (95% CI: 0.57, 0.96)] and DP with versus without prophylactic transpapillary pancreatic stenting [RR =0.45 (95% CI: 0.22, 0.94)], but there was no association between the incidence of all-grade POPF or CR-POPF with preservation of splenic vessels versus Warshaw-technique DP.

As for extraoperative-management factors, early versus late drain removal [RR =0.17 (95% CI: 0.13, 0.24)] and DP without versus with abdominal drainage [RR =0.55 (95% CI: 0.42, 0.72)] were associated with a decreased incidence of CR-POPF with low to very low quality of evidence. Passive versus active drainage was associated with an increased incidence of CR-POPF with very low quality of evidence [OR =3.35 (95% CI: 1.12, 10.07)].

POPF after other types of pancreatectomy

No outcomes associated with POPF after other types of pancreatectomy were rated as high or moderate quality of evidence (Figure 5). Only two low-quality studies suggested that CP may contribute to an increased risk of all-grade POPF [OR =2.25 (95% CI: 1.81, 2.81)] and CR-POPF [OR =2.73 (95% CI: 2.09, 3.58)] in patients with benign or low-grade malignancies localized in the pancreatic neck or body compared with DP.

Furthermore, very low-quality evidence was found for CP [OR =1.90 (95% CI: 1.46, 2.48)] and pancreatic enucleation [RR =1.46 (95% CI: 1.22, 1.75)], which were associated with an increased incidence of all-grade POPF compared with the corresponding standard procedures.

Discussion

Pancreatic fistula is one of the most common complications of pancreatic surgery (3). Many postoperative complications are directly or indirectly related to POPF, with serious complications such as intra-abdominal infection, bleeding, sepsis, and multiple organ failure syndrome (67). Thus, it is important to identify interventions related to POPF reduction. In this umbrella review, several MAs were used to investigate the influence of surgery-related factors on POPF development. A total of 82 outcomes were assessed for methodological quality, including six high, 13 moderate, 26 low, and 37 very low quality of evidence. They can be grouped into 4 categories including surgical-approach, anastomotic-method, intraoperative-management, and extraoperative-management factors.

In terms of surgical approach, the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) has not determined whether minimally invasive PD reduces the incidence of pancreatic fistula (68,69). Laparoscopic PD has been promoted mainly because of its advantages of minimal trauma, short exposure time, and a clear surgical field with camera assistance (70,71). However, our findings provide high-quality evidence that laparoscopic PD cannot reduce the incidence of pancreatic fistula compared with open PD. This may be related to the difficulty of reconstruction, bleeding control, and unskilled manipulation in a minimally invasive setting (72). It is worth mentioning that low-quality evidence found that robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery reduced the risk of CR-POPF compared with open surgery. This outcome can be explained by the advantages of precise, fine motion on multiple axes and enlarged 3D vision in robotics (73,74). However, this conclusion should be interpreted with caution because of possible selection bias and heterogeneity in the available studies. Besides, our findings confirmed, despite very low-quality evidence, that there was no difference in POPF incidence after DP compared with open surgery and laparoscopic or robotic approaches. Considering the many advantages of new technology and difficulties in technology learning, although the current results are not ideal, we believe that we should actively embrace new technology and give full play to the advantages of new and old technologies to explore a better solution.

In terms of anastomosis methods, moderate-quality evidence suggests that PG reduces the incidence of full-grade pancreatic fistula after PD compared with PJ. The effect of PG in reducing pancreatic fistula may result from the low tension of the anastomosis to ensure a good blood supply and the acidic environment of the stomach to inhibit the activity of pancreatic enzymes (75,76). In addition, studies have shown that PG has a lower incidence of ascites and shorter length of hospital stay (77). However, PJ is more popular in clinical practice (68,78), which may be because it is more in line with the natural physiological characteristics of the human body and has less impact on long-term digestive function and metabolism than PG (70,76). Furthermore, the ISGPS indicated that there was no substantial difference in the incidence of CR-POPF between PG and PJ (68), which is consistent with our findings, albeit of low quality. The two results further indicated that the effects of PG on CR-POPF and full-grade POPF were different. This reflects the fact that PG performs poorly in high-risk cases and can explain the preference for PJ when surgeons perceive an increased likelihood of fistula development (78). Consistent with this, studies have shown that PG is more effective in pancreatic head and ampullary cancers (79). Our findings indicate extremely low evidence that modified Blumgart anastomosis reduces the incidence of clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after PD compared with interrupted transpancreatic sutures. It has been reported that mattress suturing and jejunal clamping of the pancreas result in tighter anastomosis and reduce the chance of parenchymal tears, usually caused by tangential shear forces, which is beneficial in reducing pancreatic fistula (80,81). This technique is more suitable for flat and soft pancreases with small eccentric catheters (78). However, confounding bias and heterogeneity of the studies should be considered before considering this anastomosis method. Another technique is Roux-en-Y reconstruction, which is designed to separate the site of bile and pancreatic enzyme secretion into the intestine, thereby avoiding the activation of pancreatic enzymes at the anastomotic site. In our findings, high- and moderate-quality evidence showed that Roux-en-Y reconstruction did not reduce the incidence of pancreatic fistula after PD compared to single-loop reconstruction. The lack of advantage of Roux-en-Y can be explained by the greater complexity of the reconstruction process and longer duration of the procedure (82). Moderate evidence suggests that duct-to-mucosa PJ does not increase the incidence of full-grade and clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after PD compared to Invagination PJ. However, duct-to-mucosa PJ is the first choice for reconstruction after PD, as recommended by ISGPS (68). Invaginated PJ is usually an alternative when the inner diameter of the pancreatic duct is less than 3 mm and the texture is soft (76,78). These contradictory results suggest that various surgical anastomosis schemes should not be compared based on the data alone. Many factors related to the pathophysiological features of patients may lead to the development of POPF (83). Male sex, high BMI, soft pancreatic texture, and main pancreatic duct diameter <3 mm have been identified as significant risk factors for POPF (8). Familiarity with surgical techniques is also a key to reducing complications. Thus, surgeons should be flexible in selecting surgical techniques based on the unique characteristics of the patients and their own comfort and experience in performing the technique. Future research should focus on clinical study design, especially for the standardization of surgical procedures, population characteristics, and clinical outcomes.

The intraoperative management of PD remains controversial. The ISGPS concluded that during PD, there is no evidence to support the necessity of stent placement at the anastomosis or the superiority of external stents over internal stents (68). The high-quality evidence confirmed that pancreatic duct stenting and internal pancreatic duct stenting were not associated with the risk of pancreatic fistula after PD but also found that external pancreatic duct stenting significantly reduced the risk of pancreatic fistula after PD. At present, the trend of internal stents increasing the risk of pancreatic fistula eliminates the effect of external stents, reducing the risk of pancreatic fistula, resulting in the overall advantage of stents being insignificant. Internal stents have a higher risk of migration and detachment (84). The advantages of external stents are better drainage of pancreatic juice and better guidance for the placement of anastomotic sutures (26,75). However, some side effects of stents need to be considered, including substantial loss of digestive fluid, endocrine dysfunction, pancreatic duct dilatation, and potential mechanical damage (70,83,85). Generally, the role of stents is difficult to ignore. Experts often rely on stents in patients at high risk of pancreatic fistula (78). Until more high-quality, large-volume, multicenter RCTs are available, surgeons should be cautious about the results. PDO is another intraoperative treatment for PD that is different from anastomosis, aiming to avoid pancreatic enzyme activation by fundamentally separating the pancreatic fluid and intestinal contents (86). However, moderate-quality evidence from our findings confirms that PDO does not reduce the incidence of clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after PD. PDO/sealing and sealing were found to increase the risk of all-grade pancreatic fistula after PD. It has also been associated with postoperative diabetes (13). Although the available evidence does not support this technology, it does not mean that it has no value. Experts now see it as a backstop in extreme circumstances (78). From another perspective, while PDO significantly increased the risk of full-grade pancreatic fistula, it did, although not significantly, reduce the risk of a clinically relevant pancreatic fistula. This indirectly supports the conclusion that PDO can lead to the same postoperative outcomes in patients at high risk of pancreatic fistula as in those at low risk (87,88). Therefore, PDO may be a wise choice in patients with a high risk of pancreatic fistulas. Notably, ISGPS considers it to have no advantage (68). A polyglycolic acid mesh is designed to reduce pancreatic fistulas by causing an inflammatory response to promote granulation tissue infiltration into the anastomosis (89,90). However, the risk of infection exists, resulting in delayed healing of the anastomosis (91). ISGPS moderately rated tissue patches as having no advantages (68). However, we confirmed that polyglycolic acid mesh reduces the risk of clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after PD with moderate-quality evidence, and the risk of full-grade pancreatic fistula after PD with low-quality evidence. Very low-quality evidence suggests that omental/falciform ligament wrapping and artery-first PD can reduce the incidence of clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after PD. Wrapping is not clinically recommended because it is not conducive to pancreatic drainage (14). The arterial priority approach PD is beneficial for complete tumor resection and reduces bleeding, but its significance for pancreatic fistulas remains unclear (18). Moreover, moderate-quality evidence showed that standard lymphadenectomy did not significantly reduce the incidence of POPF compared to extended lymphadenectomy. Therefore, extended lymphadenectomy is also not recommended from the perspective of a pancreatic fistula, which is consistent with ISGPS (92).

In terms of extraoperative management, moderate-quality evidence suggests that there is no difference in the incidence of full-grade pancreatic fistula after PD between enteral and parenteral nutrition. Paradoxically, the ISGPS position states that enteral nutrition is superior to parenteral nutrition (93). Such recommendations are based on lower infection and complication rates, faster recovery of physiological function, and lower costs. Clinicians should choose the nutritional method according to the characteristics of the patient. Oral feeding should be permitted when the patient can tolerate pancreatic fistula (78,93). Parenteral nutrition is recommended when a patient is in a particularly poor state. Abdominal drainage after PD remains controversial. The role of drainage lies in the removal of abnormal fluid from the abdominal cavity and detection of complications. However, it can also lead to retrograde infection. Low- and very-low-quality evidence showed that no drainage or early removal of the drainage tube reduced the incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula after PD. This low-quality evidence should be treated with caution. In addition, it is clinically impractical to place no drainage tubes, which puts the patient at risk. For drainage tube removal, early drainage removal can only be performed after the evaluation of patients, almost empirically (68,78). We call for more high-quality studies on drainage after PD to establish a standard risk assessment for patients. In addition, metal stents in preoperative biliary drainage were rated as very low-quality evidence to reduce the incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula after PD.

Compared with PD, the incidence of pancreatic fistula after DP is higher, but its clinical impact is less (69). We then analyzed the factors influencing the incidence of pancreatic fistula after DP. We identified moderate-quality evidence confirming that the fibrin sealant patch did not affect the incidence of pancreatic fistula, but found that polyglycolic acid mesh was effective in reducing the incidence of pancreatic fistula. The latter, as a novel stump closure material, has not received individual attention in the DP consensus (69). However, its role in reducing pancreatic fistula is expected because of its high strength, absorbability, and sealing effect on the pancreatic stump by causing inflammatory adhesions (55,94). In our findings, evidence of low to very low quality suggests that ultrasonic dissection and prophylactic transpapillary pancreatic stenting can reduce the incidence of full-grade pancreatic fistula after DP, minimally invasive-spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy (MI-SPDP), reinforced stapler, no drainage and early removal of drainage tube can reduce the incidence of clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after DP, passive drainage increases the risk of clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after DP. This evidence is consistent with the ISGPS consensus, except for ultrasonic dissection and MI-SPDP (69). In fact, the low quality of the evidence makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions and explain inconsistent results.

The optimal extent of surgical resection of pancreatic tumors of different sizes and locations remains controversial. These disputes mainly focus on how to preserve pancreatic function maximally while achieving radical resection. Therefore, central pancreatectomy and pancreatic enucleation have been proposed. From the perspective of reducing POPF, the evidence found in this study suggests that both surgical procedures increase the risk of POPF compared to standard surgical procedures. However, from a global perspective, CP and enucleation can better protect the endocrine and exocrine functions of the pancreas and will not worsen the long-term prognosis (49-51). Since the level of evidence found in this study was relatively low, it is recommended that doctors choose the type of surgery after fully assessing the risk of POPF development.

The present umbrella review has several strengths. First, although many published MAs have summarized the evidence on various techniques to prevent POPF, there has been little synthesis of the credibility, precision, and quality of this evidence in aggregates. This study is the first to conduct an umbrella review that investigated the effects of surgery-related factors on POPF. Second, using a citation matrix combined with AMSTAR2 to identify and select overlapping MAs significantly improved the credibility of the results. Third, the GRADE was used to quantify the strength of the evidence included in this umbrella review. This allowed us to classify the strength of the evidence for each MA outcome.

This study has some limitations. The purpose of our research was to contribute to this major limitation. We did not focus on the primary outcomes of MAs other than POPF. This may not reflect the overall picture of this clinical issue. The nature of umbrella review compelled us to include systematic reviews or MAs rather than original studies, which may have prevented us from examining the latest developments related to the prevention of POPF. Because a small amount of raw data could not be accessed during the data extraction process, we had to downgrade it accordingly in the final evaluation of the quality level of the evidence. In addition, the frequency of POPF varies depending on whether it is pancreatic cancer or another condition in actual surgical procedures. Our study only focused on the effect of surgery-related factors on pancreatic fistulas. Many other factors, including patient characteristics and primary disease, cannot be considered and may bias our analyses.

In light of the above, neither minimally invasive surgery nor open surgery is superior in reducing the risk of pancreatic fistulas. PG was rated superior to PJ in terms of PD. However, it is difficult to compare the advantages and disadvantages of PG and PJ in clinical practice, and there was also no difference in the incidence of pancreatic fistula between duct-to-mucosa PJ and invaginated PJ. Roux-en-Y reconstruction has no advantage in reducing the incidence of pancreatic fistulas. External pancreatic duct stent placement can significantly reduce the risk of pancreatic fistulas after PD. PDO may increase the risk of pancreatic fistula; however, it still has application value in extreme cases. Polyglycolic acid mesh and artery-first approaches can reduce the risk of pancreatic fistulas. Extended lymphadenectomy is not recommended from the point of view of pancreatic fistula. Neither enteral nutrition nor parenteral nutrition was superior in reducing the risk of pancreatic fistulas. Early removal of drainage tubes without drainage can reduce the incidence of pancreatic fistula after PD; however, the quality of evidence is poor. As for DP, the fibrin sealant patch did not affect the incidence of pancreatic fistula, but polyglycolic acid mesh has the potential to reduce the risk of pancreatic fistula after DP. At present, there is less high-quality evidence in the field of pancreatic fistulas, especially in the field of DP. Most evidence has some limitations, such as a high risk of bias, high heterogeneity, and low standardization. Future research should focus on improving the research design and pursuing high-quality evidence. Clinicians should treat the existing evidence dialectically and deal with patients flexibly to reduce the risk of pancreatic fistulas.

Conclusions

Overall, this umbrella review identified 42 MAs, with 82 outcomes related to POPF. Of the 42 MAs, only one was rated as high quality, four as moderate, and the rest of MAs were rated as low or critically low. Among the 82 outcomes, six were supported by high-quality evidence and 13 were supported by moderate-quality evidence. Therefore, we concluded that PG, external pancreatic ductal stent, and polyglycolic acid mesh are protective factors for pancreatic fistula after PD, and PDO and sealant are risk factors for pancreatic fistula after PD. Polyglycolic acid mesh is a protective factor against pancreatic fistulas after DP. There was little difference in the incidence of pancreatic fistula in PD between minimally invasive and open surgery, duct-to-mucosa and Invaginated PJ, Roux-en-Y and conservative reconstruction, extended and standard lymphadenectomy, and in the incidence of pancreatic fistula in DP between fibrin sealant patch and no patch. These conclusions should be interpreted with caution and further confirmed according to the actual clinical situation. The remaining outcomes were supported by either low-quality or very low-quality evidence. Given the wealth of existing evidence of relatively low quality, future research should focus on the following aspects. Over-replication studies should be appropriately reduced for outcomes that have been identified as high-quality evidence. Outcomes with lower levels of evidence should focus on standardized research to improve the quality of evidence.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRIOR reporting checklist. Available at https://hbsn.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/hbsn-23-601/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://hbsn.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/hbsn-23-601/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://hbsn.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/hbsn-23-601/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Cao F, Tong X, Li A, et al. Meta-analysis of modified Blumgart anastomosis and interrupted transpancreatic suture in pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Asian J Surg 2020;43:1056-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oweira H, Mazotta A, Mehrabi A, et al. Using a Reinforced Stapler Decreases the Incidence of Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula After Distal Pancreatectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J Surg 2022;46:1969-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simon R. Complications After Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Clin North Am 2021;101:865-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005;138:8-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery 2017;161:584-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- You DD, Paik KY, Park IY, et al. Randomized controlled study of the effect of octreotide on pancreatic exocrine secretion and pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. Asian J Surg 2019;42:458-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chikhladze S, Makowiec F, Küsters S, et al. The rate of postoperative pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy is independent of the pancreatic stump closure technique - A retrospective analysis of 284 cases. Asian J Surg 2020;43:227-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kiełbowski K, Bakinowska E, Uciński R. Preoperative and intraoperative risk factors of postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy - systematic review and meta-analysis. Pol Przegl Chir 2021;93:1-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xia X, Huang C, Cen G, et al. Preoperative diabetes as a protective factor for pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2015;14:132-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara Y, Shiba H, Shirai Y, et al. Perioperative serum albumin correlates with postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Anticancer Res 2015;35:499-503. [PubMed]

- Zarzavadjian Le Bian A, Fuks D, Montali F, et al. Predicting the Severity of Pancreatic Fistula after Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Overweight and Blood Loss as Independent Risk Factors: Retrospective Analysis of 277 Patients. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2019;20:486-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- PARANOIA Study Group, Writing group. Perioperative interventions to reduce pancreatic fistula following pancreatoduodenectomy: meta-analysis. Br J Surg 2022;109:812-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chierici A, Frontali A, Granieri S, et al. Postoperative morbidity and mortality after pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatic duct occlusion compared to pancreatic anastomosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2022;24:1395-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andreasi V, Partelli S, Crippa S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the role of omental or falciform ligament wrapping during pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2020;22:1227-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mobarak S, Tarazi M, Davé MS, et al. Roux-en-Y versus single loop reconstruction in pancreaticoduodenectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2021;88:105923. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jin Y, Feng YY, Qi XG, et al. Pancreatogastrostomy vs pancreatojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: An updated meta-analysis of RCTs and our experience. World J Gastrointest Surg 2019;11:322-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kotb A, Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, et al. Meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomised controlled trials comparing standard versus extended lymphadenectomy in pancreatoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the head of pancreas. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2021;406:547-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ironside N, Barreto SG, Loveday B, et al. Meta-analysis of an artery-first approach versus standard pancreatoduodenectomy on perioperative outcomes and survival. Br J Surg 2018;105:628-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crippa S, Cirocchi R, Partelli S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of metal versus plastic stents for preoperative biliary drainage in resectable periampullary or pancreatic head tumors. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016;42:1278-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lyu Y, Cheng Y, Wang B, et al. Peritoneal drainage or no drainage after pancreaticoduodenectomy and/or distal pancreatectomy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Surg Endosc 2020;34:4991-5005. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adiamah A, Ranat R, Gomez D. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition following pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2019;21:793-801. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mungroop TH, van der Heijde N, Busch OR, et al. Randomized clinical trial and meta-analysis of the impact of a fibrin sealant patch on pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: CPR trial. BJS Open 2021;5:zrab001. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ricci C, Stocco A, Ingaldi C, et al. Trial sequential meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy: is it the time to stop the randomization? Surg Endosc 2023;37:1878-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sattari SA, Sattari AR, Makary MA, et al. Laparoscopic Versus Open Pancreatoduodenectomy in Patients With Periampullary Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2023;277:742-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takagi K, Umeda Y, Yoshida R, et al. A Systematic Review of Minimally Invasive Versus Open Radical Antegrade Modular Pancreatosplenectomy for Pancreatic Cancer. Anticancer Res 2022;42:653-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guo C, Xie B, Guo D. Does pancreatic duct stent placement lead to decreased postoperative pancreatic fistula rates after pancreaticoduodenectomy? A meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2022;103:106707. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jiang Y, Chen Q, Wang Z, et al. The Prognostic Value of External vs Internal Pancreatic Duct Stents in CR-POPF after Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Invest Surg 2021;34:738-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, et al. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:132-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Khan RMA, et al. Stapled anastomosis versus hand-sewn anastomosis of gastro/duodenojejunostomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2017;48:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hai H, Li Z, Zhang Z, et al. Duct-to-mucosa versus other types of pancreaticojejunostomy for the prevention of postoperative pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2022;3:CD013462. [PubMed]

- Wang J, Sun W, Fan Z, et al. Effect of the Type of Intraoperative Restrictive Fluid Management on the Outcome of Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2020;2020:5658685. [Crossref]

- Peng C, Zhou D, Meng L, et al. The value of combined vein resection in pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic head carcinoma: a meta-analysis. BMC Surg 2019;19:84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li T, Zhang J, Zeng J, et al. Early versus late drain removal in patients after pancreatoduodenectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Surg 2023;46:1909-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gachabayov M, Gogna S, Latifi R, et al. Passive drainage to gravity and closed-suction drainage following pancreatoduodenectomy lead to similar grade B and C postoperative pancreatic fistula rates. A meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2019;67:24-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ouyang L, Zhang J, Feng Q, et al. Robotic Versus Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy: An Up-To-Date System Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol 2022;12:834382. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang W, Huang Z, Zhang J, et al. Safety and efficacy of robot-assisted versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis of multiple worldwide centers. Updates Surg 2021;73:893-907. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yan Y, Hua Y, Chang C, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic and periampullary tumor: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and non-randomized comparative studies. Front Oncol 2022;12:1093395. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu X, Li M, Wu W, et al. The role of prophylactic transpapillary pancreatic stenting in distal pancreatectomy: a meta-analysis. Front Med 2013;7:499-505. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Bodegraven EA, van Ramshorst TME, Balduzzi A, et al. Routine abdominal drainage after distal pancreatectomy: meta-analysis. Br J Surg 2022;109:486-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xinyang Z, Taoying L, Xuli L, et al. Comparison of the complications of passive drainage and active suction drainage after pancreatectomy: A meta-analysis. Front Surg 2023;10:1122558. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen K, Liu Z, Yang B, et al. Efficacy and safety of early drain removal following pancreatic resections: a meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2023;25:485-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li P, Zhang H, Chen L, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy on perioperative outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Updates Surg 2023;75:7-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lyu Y, Cheng Y, Wang B, et al. Assessment of laparoscopic versus open distal pancreatectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 2022;31:350-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou J, Lv Z, Zou H, et al. Up-to-date comparison of robotic-assisted versus open distal pancreatectomy: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e20435. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang W, Zhang YF, Zhao YF, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic versus open radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy for pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2022;103:106676. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hang K, Zhou L, Liu H, et al. Splenic vessels preserving versus Warshaw technique in spleen preserving distal pancreatectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2022;103:106686. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou Q. Assessement of postoperative long-term survival quality and complications associated with radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy and distal pancreatectomy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Surg 2019;19:12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakata K, Shikata S, Ohtsuka T, et al. Minimally invasive preservation versus splenectomy during distal pancreatectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2018;25:476-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiao W, Zhu J, Peng L, et al. The role of central pancreatectomy in pancreatic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2018;20:896-904. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bi S, Liu Y, Dai W, et al. Effectiveness and safety of central pancreatectomy in benign or low-grade malignant pancreatic body lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2023;109:2025-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shen X, Yang X. Comparison of Outcomes of Enucleation vs. Standard Surgical Resection for Pancreatic Neoplasms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Surg 2021;8:744316. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roesel R, Bernardi L, Bonino MA, et al. Minimally-invasive versus open pancreatic enucleation: systematic review and metanalysis of short-term outcomes. HPB (Oxford) 2023;25:603-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Małczak P, Sierżęga M, Stefura T, et al. Arterial resections in pancreatic cancer - Systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2020;22:961-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lei H, Xu D, Shi X, et al. Ultrasonic Dissection versus Conventional Dissection for Pancreatic Surgery: A Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2016;2016:6195426. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang W, Wei Z, Che X. Effect of polyglycolic acid mesh for prevention of pancreatic fistula after pancreatectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e21456. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liao Z, Fang Z, Gou S, et al. The role of diet in renal cell carcinoma incidence: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. BMC Med 2022;20:39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shojania KG, Sampson M, Ansari MT, et al. How quickly do systematic reviews go out of date? A survival analysis. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:224-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, et al. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Senn SJ. Overstating the evidence: double counting in meta-analysis and related problems. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bougioukas KI, Liakos A, Tsapas A, et al. Preferred reporting items for overviews of systematic reviews including harms checklist: a pilot tool to be used for balanced reporting of benefits and harms. J Clin Epidemiol 2018;93:9-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pieper D, Antoine SL, Mathes T, et al. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:368-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017;358:j4008. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328:1490. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fusar-Poli P, Radua J. Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evid Based Ment Health 2018;21:95-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4002. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Machado NO. Pancreatic fistula after pancreatectomy: definitions, risk factors, preventive measures, and management-review. Int J Surg Oncol 2012;2012:602478. [PubMed]

- Shrikhande SV, Sivasanker M, Vollmer CM, et al. Pancreatic anastomosis after pancreatoduodenectomy: A position statement by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2017;161:1221-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miao Y, Lu Z, Yeo CJ, et al. Management of the pancreatic transection plane after left (distal) pancreatectomy: Expert consensus guidelines by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2020;168:72-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kawaida H, Kono H, Hosomura N, et al. Surgical techniques and postoperative management to prevent postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreatic surgery. World J Gastroenterol 2019;25:3722-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ammori BJ, Ayiomamitis GD. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy: a UK experience and a systematic review of the literature. Surg Endosc 2011;25:2084-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang M, Cai H, Meng L, et al. Minimally invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy: A comprehensive review. Int J Surg 2016;35:139-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boggi U, Amorese G, Vistoli F, et al. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic literature review. Surg Endosc 2015;29:9-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boggi U, Signori S, De Lio N, et al. Feasibility of robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 2013;100:917-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zovak M, Mužina Mišić D, Glavčić G. Pancreatic surgery: evolution and current tailored approach. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2014;3:247-58. [PubMed]

- Chen YJ, Lai EC, Lau WY, et al. Enteric reconstruction of pancreatic stump following pancreaticoduodenectomy: a review of the literature. Int J Surg 2014;12:706-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu FB, Chen JM, Geng W, et al. Pancreaticogastrostomy is associated with significantly less pancreatic fistula than pancreaticojejunostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:123-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Casciani F, Bassi C, Vollmer CM Jr. Decision points in pancreatoduodenectomy: Insights from the contemporary experts on prevention, mitigation, and management of postoperative pancreatic fistula. Surgery 2021;170:889-909. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin RF, Zuberi KA. The evidence for technical considerations in pancreatic resections for malignancy. Surg Clin North Am 2010;90:265-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grobmyer SR, Kooby D, Blumgart LH, et al. Novel pancreaticojejunostomy with a low rate of anastomotic failure-related complications. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210:54-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Satoi S, Yamamoto T, Yanagimoto H, et al. Does modified Blumgart anastomosis without intra-pancreatic ductal stenting reduce post-operative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticojejunostomy? Asian J Surg 2019;42:343-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perwaiz A, Singhal D, Singh A, et al. Is isolated Roux loop pancreaticojejunostomy superior to conventional reconstruction in pancreaticoduodenectomy? HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:326-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hackert T, Werner J, Büchler MW. Postoperative pancreatic fistula. Surgeon 2011;9:211-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan AW, Agarwal AK, Davidson BR. Isolated Roux Loop duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy avoids pancreatic leaks in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Dig Surg 2002;19:199-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaman L, Nusrath S, Dahiya D, et al. External stenting of pancreaticojejunostomy anastomosis and pancreatic duct after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Updates Surg 2012;64:257-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith HS, Ghosh BC, Huvos AG. Ligation versus implantation of the pancreatic duct after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1971;132:87-92. [PubMed]

- Mazzaferro V, Virdis M, Sposito C, et al. Permanent Pancreatic Duct Occlusion With Neoprene-based Glue Injection After Pancreatoduodenectomy at High Risk of Pancreatic Fistula: A Prospective Clinical Study. Ann Surg 2019;270:791-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giglio MC, Cassese G, Tomassini F, et al. Post-operative morbidity following pancreatic duct occlusion without anastomosis after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2020;22:1092-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ceonzo K, Gaynor A, Shaffer L, et al. Polyglycolic acid-induced inflammation: role of hydrolysis and resulting complement activation. Tissue Eng 2006;12:301-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jang JY, Shin YC, Han Y, et al. Effect of Polyglycolic Acid Mesh for Prevention of Pancreatic Fistula Following Distal Pancreatectomy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg 2017;152:150-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wolf SE, Ridgeway CA, Van Way CW, et al. Infectious sequelae in the use of polyglycolic acid mesh for splenic salvage with intraperitoneal contamination. J Surg Res 1996;61:433-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tol JA, Gouma DJ, Bassi C, et al. Definition of a standard lymphadenectomy in surgery for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a consensus statement by the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2014;156:591-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gianotti L, Besselink MG, Sandini M, et al. Nutritional support and therapy in pancreatic surgery: A position paper of the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2018;164:1035-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Juo YY, Hines OJ. Polyglycolic Acid Mesh in Distal Pancreatectomy: A Tool for Preventing Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula? JAMA Surg 2017;152:156. [Crossref] [PubMed]