Bladder peritoneal flap: a novel approach for pelvic peritoneal reconstruction in complex clinical cases

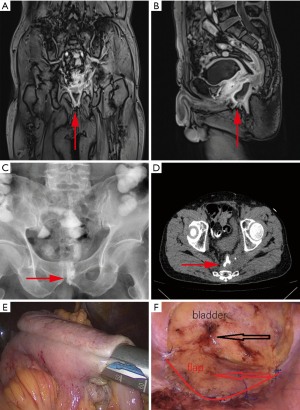

A 60-year-old male was diagnosed with rectal cancer with peripheral lymph node metastasis two years prior and underwent three cycles of the XELOX (capecitabine plus oxaliplatin) chemotherapy regimen, followed by radiotherapy and a successful laparoscopic radical resection of the rectal carcinoma, with a postoperative pathological stage of T4N3M0. One month prior, he received additional radiotherapy due to metastasis in the left ischiatic region. He was referred to our hospital with swelling, pain in the perineal and gluteal regions around the anus, and fever following radiotherapy. Laboratory investigations revealed leucocytosis (20×109/mL) and an elevated C-reactive protein level (78.94 mg/dL), while subsequent imaging identified an intestinal fistula (Figure 1A-1D) and pelvic infection. His medical history included a subtotal gastrectomy performed 30 years ago for a perforated peptic ulcer. On admission, physical examination demonstrated significant tenderness at the base of the left thigh near the perineum, with surrounding skin exhibiting erythema and swelling, though no ulceration was observed.

In March 2024, the patient underwent laparoscopic surgery, during which a segment of the ileum, approximately 60 cm in length, had descended into the pelvic floor and adhered to the pelvic wall, leading to the formation of an intestinal fistula. Consequently, a decision was made to excise the affected bowel segment and perform an anastomosis (Figure 1E).

Considering that the patient underwent radiotherapy after surgery and other methods of pelvic peritoneal reconstruction (PPR) were not feasible, a decision was made to perform PPR using a bladder peritoneal flap.

Briefly, the operation involved the following:

- Under laparoscopic visualisation, the peritoneum was first incised. The bladder peritoneal flap, shaped like an arch or an “n”, was carefully dissected from the bladder.

- Sharp dissection in close proximity to the muscular layer of the bladder, combined with blunt separation, was performed to preserve an adequate blood supply to the flap.

- The flap was then rotated to cover the entrance of the pelvic cavity. Closure was achieved using a running suture, securing the free edge of the flap to the pelvic brim. The procedure was conducted gently to avoid injury to the anterior sacral vessels (Figure 1F).

The procedure was successfully completed laparoscopically, with a total operative duration of 150 minutes and an estimated blood loss of approximately 20 mL. The patient recovered well from anaesthesia and was safely transferred to the ward.

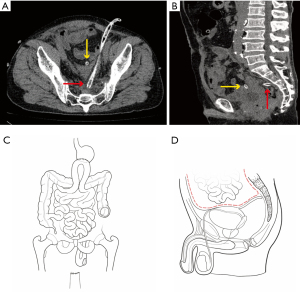

After surgery, the patient’s pelvic cavity was isolated by the bladder peritoneum flap to form an independent space and the small intestine was isolated within the abdominal cavity.

Finally, a drainage tube was placed in both the abdominal cavity and the pelvic cavity to prevent abscess formation (Figure 2A,2B), which is essential for patients with abdominal infections. The preoperative and postoperative abdominal conditions of the patients are shown in Figure 2C and Figure 2D. These drainage tubes were removed 2 weeks postoperatively. On the 15th day after surgery, the patient had recovered well and was discharged without complications.

At present, the patient received 1 course of radiotherapy and 3 courses of chemotherapy, and no postoperative complications were found.

Empty pelvis syndrome (EPS) is defined as a complication that arises due to the empty space created following extensive pelvic surgery involving perineal resection. This condition can lead to fluid accumulation and bowel translocation within the pelvic cavity, increasing the risk of pelvic abscess formation, perineal fluid discharge, perineal wound dehiscence, and prolonged ileus (1). Consequently, EPS represents a significant yet underrecognized postoperative complication that poses challenges for both patients and surgeons. Despite ongoing advancements, the prevention and management of EPS remain complex, with no standardised treatment protocol currently established. Various preventive strategies have been employed; however, each approach carries its own associated risks and complications.

PPR is an effective strategy to prevent the descent of abdominal contents into the pelvic floor and limit the spread of inflammation, thereby reducing the incidence of EPS (2). PPR techniques can be broadly classified into partition techniques and filling techniques. Partition techniques involve creating a physical barrier to separate the abdominal and pelvic cavities using a closed pelvic peritoneum, prosthetic materials, or surgical mesh. In contrast, filling techniques aim to occupy the pelvic dead space with structures such as pedicled omentoplasty, myofascial flaps, or breast prostheses, preventing fluid accumulation and organ displacement (3).

Despite various PPR methods, reconstruction failed due to the insufficiency of the greater omentum and mesentery, the inability to dissociate the abdominal wall muscles due to the colostomy, and the contraindication of mesh use in the presence of pelvic infection (4). Consequently, the bladder peritoneal flap was selected for PPR, which resulted in a favourable outcome.

To the present knowledge, this is the first clinical report documenting the application of this novel technique in such a complex and challenging case. This report demonstrates the short-term effectiveness and safety of this approach in selected patients, facilitating the possibility of follow-up treatment. We believe this new method is feasible and hope that more patients undergo this procedure to further validate its effectiveness and feasibility.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was a standard submission to the journal. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at https://hbsn.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/hbsn-2024-765/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://hbsn.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/hbsn-2024-765/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying image resources.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Lee P, Tan WJ, Brown KGM, et al. Addressing the empty pelvic syndrome following total pelvic exenteration: does mesh reconstruction help? Colorectal Dis 2019;21:365-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Yang X, Hao M. The value of pelvic peritoneal reconstruction during abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024;103:e41035. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa S, Yokogawa H, Sato T, et al. Gluteal fold flap for pelvic and perineal reconstruction following total pelvic exenteration. JPRAS Open 2019;19:45-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Musters GD, Klaver CEL, Bosker RJI, et al. Biological Mesh Closure of the Pelvic Floor After Extralevator Abdominoperineal Resection for Rectal Cancer: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial (the BIOPEX-study). Ann Surg 2017;265:1074-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]