When technology fails: the pivotal role of meticulous clinical reasoning in unmasking an invisible colon cancer mimicking chronic ischemic colitis

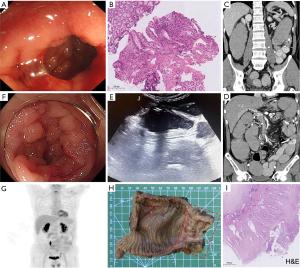

A 49-year-old male was admitted with a 9-month history of intermittent abdominal pain and a 2-day cessation of exhaust and defecation. He had no history of metabolic disorders, malignancy, or relevant family history. At disease onset, he experienced sudden, severe upper abdominal pain radiating to the back. Enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed a localized dissection of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) with mural thrombosis in the false lumen. Gastroscopy and colonoscopy showed isolated left descending colon stenosis with rough mucosa (Figure 1A), and multipoint deep biopsies suggested suspected ischemia and no hints of malignancy (Figure 1B). He was diagnosed with chronic ischemic colitis but adhered irregularly to anticoagulant therapy. He experienced intermittent periumbilical pain for the next 9 months until he eventually developed bowel obstruction and was transferred to Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Repeated enhanced CT revealed progressive colonic stenosis leading to mechanical obstruction, without an identifiable mass or lymphadenopathy (Figure 1C), although the SMA dissection remained stable without distal blood supply impairment (Figure 1D). Intestinal ultrasound showed clear-layered thickening of the stenotic bowel wall (Figure 1E). Colonoscopy was re-examined and confirmed progressive stenosis with swelling and inflamed mucosa (Figure 1F), with pathological biopsies supporting the previous conclusions. Tumor markers, thrombophilia screening, infection and immune indicators were negative, and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET)/CT showed no abnormal hypermetabolic lesions (Figure 1G). Active gastrointestinal decompression and anticoagulant therapy were given and his symptoms partially improved.

Since all accessible tests were negative for tumor screening and uncontrolled symptoms could be attributed to patients’ poor compliance, chronic ischemic colitis seemed to the reasonable diagnosis and placement of covered stent or balloon dilatation could be the available treatment options if conservative treatment did not take effect. However, rethinking the patient’s entire medical history with the eyes of a detective rather than only focusing on examinations, things was not really the case. First, the left colon’s blood supply does not originate from SMA, and the dissection did not affect the distal blood supply as demonstrated by the enhanced CT, although the colonic stenosis was in a predilection site of ischemia (1,2). Second, the chronic stenosis was not consistent with the acute course of abdominal pain at disease onset. Third, vascular dissection was commonly secondary to uncontrolled hypertension while the patient denied medical history of metabolic disorders. As a result, a careful retrospective review of the patient’s clinical history was performed and it was noting that the male remembered he had experienced newly emerged difficult defecation with frequent excessive force and reddening face 6 months before disease onset, which was possibly attributed to undiscovered colon stenosis and could potentially explain the vascular dissection. Therefore, the real medical story turned to that an isolated worsening colon stenosis inconsistent with ischemic colitis occurred in a middle-aged male, in which malignant tumor was highly suspected. Laparoscopic exploration was pursued following multidisciplinary discussion. The intraoperative frozen pathological results indicated adenocarcinoma, and thus surgical approach was timely adjusted to radical resection of left colon cancer. Postoperative gross and paraffin pathology finally confirmed the invisible diagnosis of diffuse infiltrative and moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, with muscularis propria invasion and one twenty thirds regional lymph node metastasis (Figure 1H,1I). The immunohistochemical staining of caudal-related homeobox 2 (CDX2) was positive, suggesting colon origin. Further whole genome analysis denied significant mutations. Subsequently, the male discharged to the oncology department for further chemotherapy.

Diffuse infiltrating colorectal cancer is characterized by infiltrating growth, a nearly normal mucosal surface, a tendency for low differentiation and metastasis, and a poor prognosis (3). Up to now, combination of multiple accessible non-invasive methods and invasive multipoint deep biopsies basically could contribute to the accurate diagnosis or important hints for malignancy (4). Nevertheless, the difficulty in diagnosis occurred in this case with nearly missing tumor following failure of adequate assessment although isolated short-segment colonic strictures and progressive clinical course occurring in a middle-aged male in this case warranted a high index of suspicion for colon cancer as a leading differential diagnosis. We speculated the reason was possibly attributed to the rare tumor characteristics with moderate differentiation and diffuse infiltrating growth simultaneously. The former mainly invaded locally rather than early metastasis in low-differentiated tumors, and the latter presented nearly normal mucosa difficult to get positive biopsy specimens from endoscopy. In addition, it was also rare to find advanced cancer with negative 18F-FDG-PET/CT scan findings in this case, a phenomenon mostly observed in signet-ring cell carcinoma due to low expression of glucose transporter-1, or mucinous adenocarcinomas due to their high mucin content and low cellularity (5,6). Notably, the ischemic colitis observed histologically in this case lacked specificity and likely represented secondary changes due to tumor infiltration or mechanical compression of local vasculature, rather than a primary ischemic pathology. In a word, this case recalls the importance of detective-like perception and meticulous clinical reasoning as the unique nature of clinicians, especially when advanced technology such as artificial intelligence (AI) are currently widely used in medical field (7). While AI offers powerful diagnostic tools, it also sparks debates about the balance between human judgment and algorithmic reliance (8). In an era of human-machine collaboration, clinicians must remain vigilant interpreters of technology, integrating AI-derived insights with patient-centered reasoning to avoid diagnostic complacency (9).

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was a standard submission to the journal. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at https://hbsn.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/hbsn-2025-152/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://hbsn.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/hbsn-2025-152/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Skinner D, Wehrle CJ, Van Fossen K. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Inferior Mesenteric Artery. Treasure Island, FL, USA: StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Wan D, Bruni SG, Dufton JA, et al. Differential Diagnosis of Colonic Strictures: Pictorial Review With Illustrations from Computed Tomography Colonography. Can Assoc Radiol J 2015;66:259-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jass JR, Ajioka Y, Allen JP, et al. Assessment of invasive growth pattern and lymphocytic infiltration in colorectal cancer. Histopathology 1996;28:543-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kekelidze M, D'Errico L, Pansini M, et al. Colorectal cancer: current imaging methods and future perspectives for the diagnosis, staging and therapeutic response evaluation. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:8502-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dondi F, Albano D, Giubbini R, et al. 18F-FDG PET and PET/CT for the evaluation of gastric signet ring cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Nucl Med Commun 2021;42:1293-300. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Whiteford MH, Whiteford HM, Yee LF, et al. Usefulness of FDG-PET scan in the assessment of suspected metastatic or recurrent adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:759-67; discussion 767-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kurian M, Adashek JJ, West HJ. Cancer Care in the Era of Artificial Intelligence. JAMA Oncol 2024;10:683. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rampton V. Artificial intelligence versus clinicians. BMJ 2020;369:m1326. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu KH, Healey E, Leong TY, et al. Medical Artificial Intelligence and Human Values. N Engl J Med 2024;390:1895-904. [Crossref] [PubMed]